The great white shark is listed as vulnerable on the endangered species list.

Found in cool, coastal waters around the world, great whites are the largest predatory fish on earth. They grow to an average of 15 feet in length, though specimens exceeding 20 feet and weighing up to 5,000 pounds have been recorded. They can live 70 years or longer. White shark populations in U.S. waters are unknown.

The white shark is partially warm-blooded and can maintain its internal body temperature above that of the surrounding water. This means that it can be a more active predator in cooler waters compared to cold-blooded species.

Great white sharks are known to be highly migratory, with individuals making long migrations every year. In the eastern Pacific Ocean, great whites regularly migrate between Mexico and Hawaii. In other ocean basins, individuals may migrate even longer distances.

The white shark grows slowly. Males mature at approximately 26 years of age and females at approximately 33 years.

Like in many highly migratory species, the very largest individuals are female. Great whites mate via internal fertilization and give live birth to a small number of large young. Though they give live birth, great whites do not connect to their young through a placenta. Instead, during the gestation period, the mother provides her young with unfertilized eggs that they actively eat for nourishment. After they are born, young great whites are already natural predators, and they eat coastal fish.

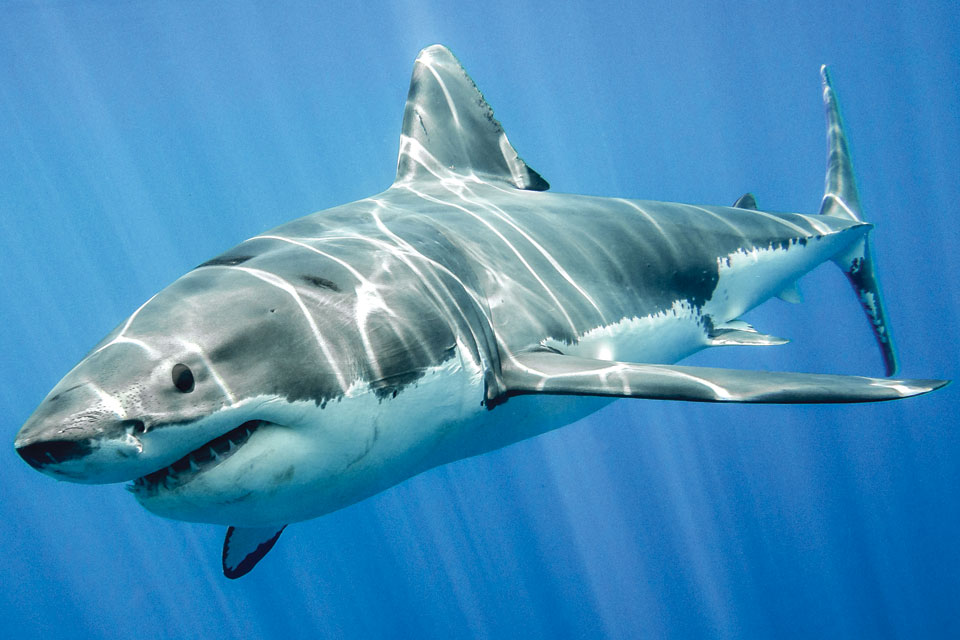

The shark’s heavy, torpedo-shaped body allows it to cruise efficiently for long periods of time, and then suddenly switch to high-speed bursts in pursuit of prey. It feeds on a broad spectrum of prey, from small fish, such as halibut, to large seals and dolphins. They have 300 teeth but do not chew their food. Sharks rip their prey into mouth-sized pieces which are swallowed whole. The great white is capable of eating marine mammals that weigh several hundred pounds.

More than one-third of all sharks are now at risk of extinction because of overfishing, according to a new study re-assessing their IUCN Red List of Threatened Species extinction risk status. Governments and regional fisheries bodies must act now to stop overfishing and prevent a global extinction crisis.

Sharks play many key roles in the ocean, shaping it for millions of years. These animals are indispensable to ocean health and to the well-being of millions of people across the globe through the food, livelihoods, and tourism opportunities they provide.